Our Collective Responsibility for Moumita Debnath

Examining the role of spirituality and ancestral healing in confronting gender-based violence and sustaining social movements

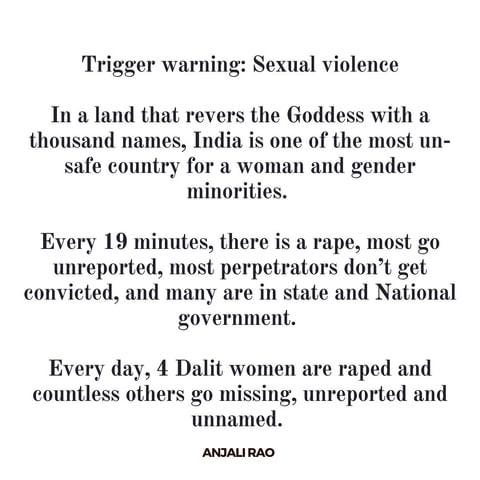

It’s not lost on me that in the same week I shared writing on the pantheon of revered goddesses in the South Asian tradition, another instance of horrifying gender based violence has left my community reeling.

Today’s issue will explore themes of sexual violence. Please skip if this is not for you today.

Outline:

Say Her Name: Moumita’s Story

Why Moumita’s Story Matters in the West

Revolutionary Spirituality

Ancestral Healing through Confronting Contradictions

Offerings

Say Her Name: Moumita’s Story

Moumita Debnath was a 31-year old resident physician in Kolkatta who was brutally gang raped and murdered while taking a nap after a 36 hour shift.

Protests have erupted around the country. Doctors have been on strike demanding justice and safer working conditions. Sadly Moumita’s story is not an isolated incident, but rather a flashpoint in a long bloody legacy of women martyrs and survivors of sexual violence in South Asia.

It also must be noted that Moumita’s story has made global headlines because of the extreme nature of the case *and* because she’s a caste-privileged woman. Lower-caste, Dalit, Muslim women suffer sexual violence daily in extremely high numbers. These cases go unreported due to cultural stigma or unresolved due to the ineffectiveness of the justice system. Culturally, this violence against women is normalized, accepted, and concealed.

In our disbelief, through our horror, we South Asians are left confronting complexity. How is it that in our ancient religion and our oldest scriptures, we had a sacred and profound relationship to Nature, and Women were revered as spiritual equals, but today we don’t collectively put this into practice?

How is it that our oldest philosophies teach us to see the divinity in all living and non-living beings, but the same scriptures have been twisted to justify caste hierarchy?

How is it today goddesses are worshipped daily in our home altars and temple rituals, and yet the violence gender-based violence has proliferated unendingly?

Why Moumita’s Story Matters in the West

I’ve seen a few palm-colored people reminiscing on their spiritual treks to India, bittersweetly reflecting on how they too never felt safe in this country despite loooving the culture and the colors. They’re disgusted by and distance themselves from the patriarchal and sexually repressed culture that is killing the vibe of their spiritual playground.

White people and Westerners have stolen our names, our style, our culture, our labor, our indigenous wisdom and re-packaged and appropriated it for their own material and spiritual benefit. And then when it suits them, they turn away from reality, as if they’re not the inheritors and benefitors of the imperial violence that maintains this vast bloody hierarchy of violence around the globe.

They don’t see the tens of thousands protesting demanding change from rigid and corrupt governments. They don’t see the millions more grieving and raging. They don’t see the South Asian men of honor, the feminists, the cycle breakers who have fought and strived to protect and promote the independence of the women in their family. They overlook the countless radical women, femmes, and queers who have fought to evolve the conservative culture, through their work and by simply being who they are.

More importantly, they don’t see the connection between Hindu fascism, the global legacy of colonialism, and the continued rise of the conservative right in America. They live in fear that Trump will bring on a Handmaid’s Tale-like dystopia, without realizing how much it’s already here. They choose to ignore the state violence that takes place in the US and abroad, turning away from and denying culpability in genocide and the growing policrises.

They see themselves separate, distinct from, better than, more enlightened.

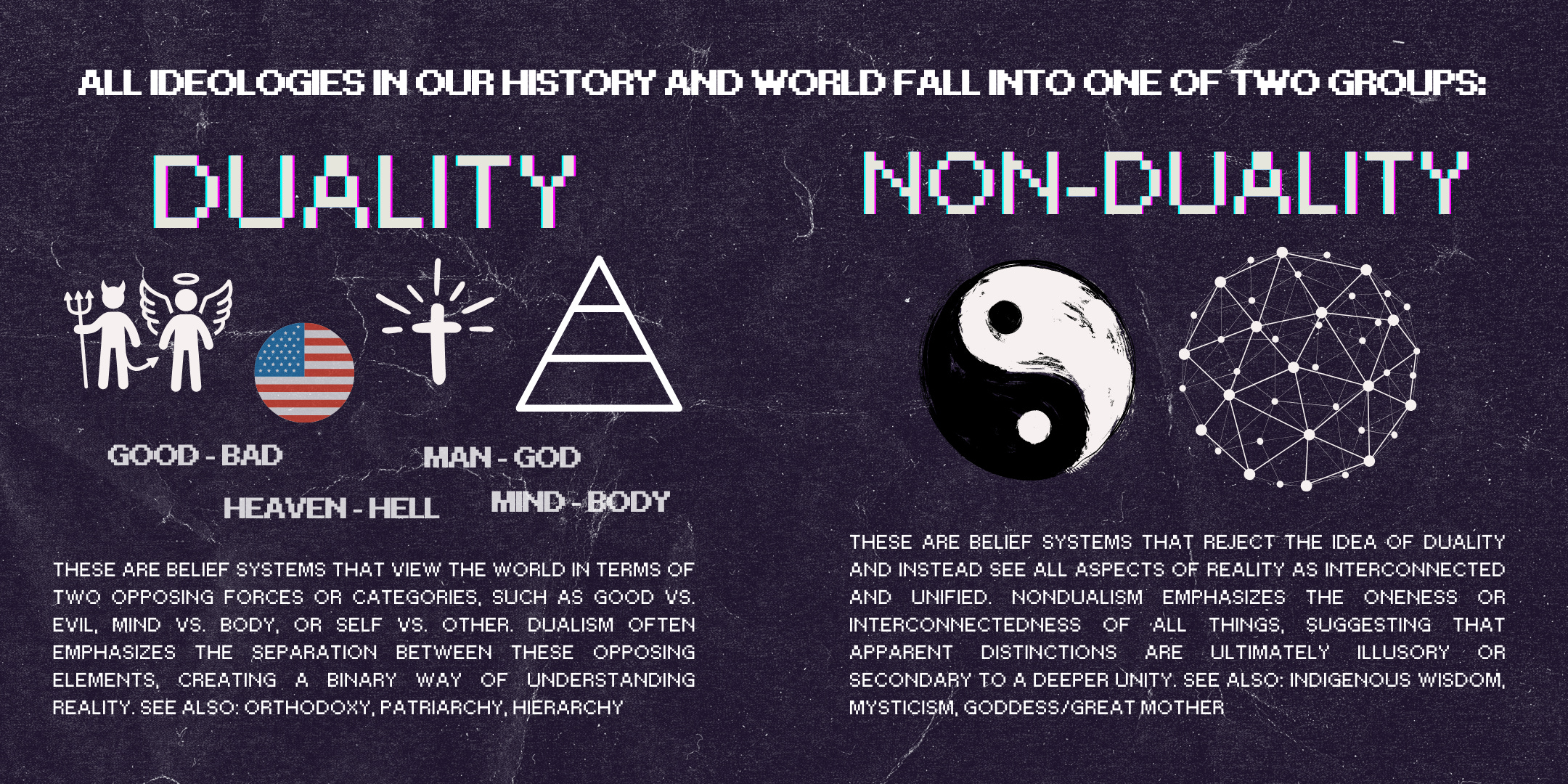

This illusion of separation is a byproduct of the dualistic and individualistic worldview that is part and parcel of American cultural conditioning.

Meaning - while it’s easy for me to rail against White people stealing and appropriating culture, the truth is that ALL OF US participate in varying degrees, consciously and unconsciously, in the status quo.

Revolutionary Spirituality

There’s a reason why I write about spirituality as the solution to our greatest social and political problems today.

Dualistic belief systems are what have resulted in our paradigm of capitalist and colonial violence, oppression, exploitation. Nondualistic beliefs and practice hold the key to our healing and liberation.

When it comes to political organizing and social movements, understanding nondual philosophies is actually so key. Because while historically social movements have succeeded through building collective power and seeing all liberation struggles as connected, there are so many examples of how progressive social movements have fallen apart by dualistic ideologies.

This is what happens when we reduce movements to solely being about alleviating the oppression of one social group, or when the internal culture of the movement is rife with issues of hierachy, power dynamics, exclusion, and individualism. We become what we fear and are fighting against - ego-driven, corrupt, unable to navigate conflict generatively, tearing each other down, leaving every man for himself.

Without understanding our unconscious spirituality - the values, beliefs, and stories we hold that shape our worldviews - and without shaping it consciously towards a vision for healing and liberation that sees all humans and earth as connected, we will fail to make the change we seek.

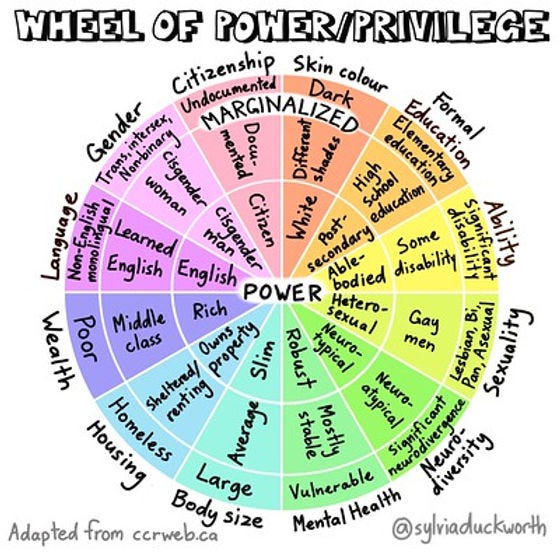

Nonduality also helps us elevate political praxis beyond identity politics.

So much of why liberalism is a hollow attempt at moving progressive movements forward is because what binds it together is the belief that identity politics is what will save us.

Liberalism tells us a simple story of who is the oppressor, who is oppressed, and who will save us (usually it’s one hero/heroine in the form of an elected official. Let’s BFFR).1

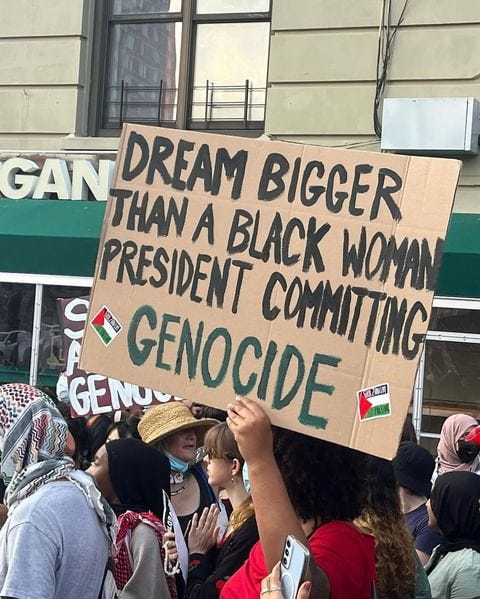

We shortsightedly believe that liberation will be achieved incrementally just if we get more women, more Black and brown faces into positions of power.

We believe that *we* will make things better - as soon as we have accumulated enough power, clout, money, and safety. Funny how we never seem to have enough to begin taking those personal and strategic risks to disrupt the status quo. If anything, we just cling even harder to what makes us feel safe.

We find it easier and safer to coalesce with people who share our identities and our political views, and further and further, we shut out anyone who slightly disagrees with us.

We’re playing into the colonizer’s handbook when we have isolationist and puritanical approaches to building community and movements.

I’m mostly left wondering how inclusive (or not) feminist movements have been to men and what our role is in changing this. It’s an uncomfortable question to explore. Whether we like it or not, while women have progressively pursued empowerment and liberation in all spheres of life, men are eating themselves and everyone around them alive through Incel culture. I highly recommend this episode on Liberation Psychology and psychologist Harriet Fraad’s reflection on this conundrum in the second half of the episode:

I hope it’s not too obvious to say that we live in a day and age where masculinity worships women in theory and harms us in practice, largley due to their own unchecked shadow, baggage, and inherited stories around masculinity. bell hooks’ The Will To Change is a must read on this topic, where she talks about all the ways in which young boys and men have been denied love and how cycles of violence persist because we’ve collectively failed men in supporting their emotional wellbeing.

The overly simple stories of hero-monster do not serve us any more. There is not a single social group immune from the complexity of holding dual, conflicting identities. Especially for those of us who aren’t Black, Native, Lower-Caste, for those of us who don’t have highly politicized identities - we have a mixed bag of identities and privileges that seat us squarely in the nonbinary land of oppressor and oppressed, colonizer and colonized.

So what do we do about it?

Ancestral Healing through Confronting Contradictions

I can only really speak from my positionality and my point of view. But every single person reading this has a similar set of tasks to undertake when it comes to ancestral healing.

For those of us in the South Asian diaspora like me who are upper-caste and have in our family system achieved class mobility, we straddle binary identities and our learned stories are often at odds with each other because we inherited both dualistic and nondualistic ways of seeing the world.

Our ancient spiritual traditions teach us to revere the Goddess and to marvel at the divinity of Nature, but from these same roots emerged the caste hierarchy and religious patriarchy that exists today.

In my family, I come from spiritualists, creatives, disruptors, activists. At home, I learned about how God resides in everything and everyone, even in the tiniest of bugs or a discarded piece of paper.

But I also learned expectations of what behavior was good and bad, that God was always watching me, and that I should at all costs avoid bringing shame to my family. This included how I behaved, the profession I’d choose, the choices I made about my body.

On the one hand, the first feminists I knew were the strong, vocal, and unecquivcally supportive men in my family. These were men who wanted the best for their daughters, including an education, all the way up to full independence, autonomy, and security.

On the other hand, I also learned cultural expectations around what it means to be an acceptable woman, perfect and pure, which included obeying authority as a matter of propriety and common sense. I learned that it was my responsibility to protect myself against sexual violence.

My family’s story largely centered around the importance of education and achieving financial success and security, because only a handful of generations ago our family suffered poverty and famine. Every generation in our familial memory suffered to provide better opportunity for its descendants, and only through the slimmest of chances were we able to lift ourselves out of poverty. It was all done for the love and care for the children.

But this single story conceals the reality that as Brahmins, it was not only our hard work that contributed to our story of success. We had proximity to literacy, education, and opportunity in a way that the vast majority in India still to this day are denied.

As an immigrant family, we were thrilled to be a part of the “melting pot” of America, beautiful in its diversity of cultures and backgrounds, utopic in its seemingly endless expanse of opportunity that was beyond our ancestors’ wildest dreams.

But the cost we paid was through assimilation, upholding the myth of the model minority, and repressing our traumas.

Did you know that confronting cognitive disonance is a requisite part of learning or shifting mental models, but physiologically when we do this we experience pain?

It makes sense why it’s easier to ignore this work.

I think anyone can relate to the idea of inheriting conflicting ideas and stories. We are constantly practicing holding multiple truths, considering both, and. This is the work of ancestral healing. When we do the challenging work of teasing out our complex inherited stories, we disrupt the reductionist identity politics of the liberal West that ultimately preserves the status quo.

Especially as diasporic women of color, we feel deep pain and grief when we relate to Moumita's story. It’s easy to look outwards and blame men, blame the legacy of colonialism, blame corrupt government, blame uneducated and “backwards” culture, and take a sigh of relief with gratitude that the blood, sweat, and tears of our ancestors has resulted in a modicum of safety and freedom for us.

I will never understand the mystery of why there is so much senseless suffering in the world and why my lot in life has me ended up here in this space, this body, this moment in time, here writing to you about my thoughts on what we might do about this endless suffering. But I do know we do the opressor’s work for them when we choose to remain silent, frozen in our instincts for self-preservation, and do nothing.

What if instead we saw ourselves as divine channels of creativity, healing, consciousness raising, CHANGE?! We each have power - through our creativity, our intelligence, our fire, our courage, our influence, our voice, our capacity to love. All we have is the gumption to defy the status quo, while learning to weild our power and our gifts with consciousness and creativity for good.

I’ll be sharing more on this topic next week, stay tuned.

Offerings

If you’re in the Bay Area this weekend, join me as I do the contradiction-heavy work of reclaiming Tantra from its exported and distorted Western understanding. Learn more and register here.

For fellow Desis, this will be an incredible place to continue ancestral healing work through confronting contradictions. Learn more and register here.

Really incredible class being hosted by Night School Bar. Learn more and register here.

Decolonial Thoughts is inviting artists, writers, and scholars to contribute to their upcoming series on Truth: Unmasking the Lies that Sustain Oppression. looking for submissions that delve into uncomfortable truths and the lies that shape systems of violence. Due September 6th.

A free training from Aorta on Queer and Trans Liberation as Collective Liberation. Aorta doesn’t offer free trainings often and this collaboration with the School of Making and Thinking will be dope. Register here.

This is not about voting for or not voting for Kamala. I respect the choices across the gamut, those who are in principle not voting for her for her facilitation of Palestinian genocide or in pragmaticism choosing to vote for her strategically because organizing uner her administration will be a hell of a lot different than under Trump’s. But I do think that seeing a Black and Brown woman in the highest office of this land as a marker of progress is misguided.